The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic across the world has been of grave concern for all. The tragic loss of life, the strain to the health-service, the anxiety caused by isolation, and the uncertainty of the future are just some of the most salient things that we must face together.

Our first response at LSFRC was to cancel all our upcoming events and group meetings in order to help slow the spread of the virus. We subsequently decided to go ahead with the meetings in an online form.

We took this decision for a couple of reasons. Firstly, we believe that our community can provide a support network in these uncertain times, building on the community that we have nurtured over the last five years. We hope these meetings can provide some comfort and solace for those of us isolated from each other.

Secondly, we think our year’s theme of borders has never been more relevant. The Covid-19 crisis has seen the hardening of borders across the world, both within and without the boundaries of the state. National borders are closed to migrants while new restrictions on migrant camps across Europe put our most powerless at risk. Similarly, within state lines, institutions such as detention centres and prisons enclose individuals together who do not have the freedom to self-isolate. As one doctor working in the Lesbos migrant camp, Steven van de Vijver, has put it ‘Coronavirus does not respect borders or barbed wire.’ At the same time, Mutual Aid groups of all kinds, popping up across the country, have reached out across the borders of age, class, and community to protect those whose bodily borders are most vulnerable to the virus. Our current crisis is therefore very much one of borders, making us fundamentally rethink their function, in a way we recognise from the denaturing effect at the heart of science fiction.

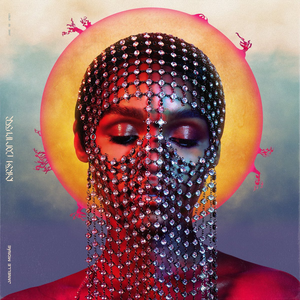

We therefore went ahead with our April meeting in which we were due to discuss Dirty Computer the 2018 emotion picture by Janelle Monáe. We held a collective online viewing of the visual album at 6pm on the 6th April, on the platform watch2gether and we then moved onto Zoom for a discussion lasting from around 7 until 8.30 pm. We began with some etiquette for speaking, before diving into a high quality discussion, which took place both on audio and on the text chat function. I am going to attempt to summarise the points made on the audio but not so much the chat, as I was unable to take notes on both as they were running concurrently. The chat was, though, a wild ride of associations and references, at some points riffing off the audio discussion and at some points taking its own direction.

Themes

Form

We discussed various elements of the form of the album in detail. We began by debating the merits of the framing narrative which links all the songs together. Some felt the framing narrative to be unsatisfactory and thin while others praised it for highlighting the politics of memory (see section on Memory below). Further, the framing narrative foregrounded the science fictional elements of the individual songs, which might have been missed if not placed within a more overt science fiction setting. There was also, it was suggested, an effective juxtaposition of the shiny oppressive aesthetic of the frame narrative with the vibrant look of the songs themselves, hinting at a divide between institutional and racist orthodoxy and the liminal spaces of hope at its edges. One participant astutely observed that the variety of aesthetic styles deployed in the different music videos contrasted with the aesthetic flattening common to much sf film where it frequently seems that everyone in the future will wear the same uniform.

We further discussed the form of the album film itself, referencing its connection with recent projects such as Beyoncé’s Lemonade as well as older works like Sun Ra’s Space is the Place which we watched earlier this year.

We also considered the three different endings. The three endings were compared with the multiple endings of David Cronenberg films (specifically eXistenZ) and thought they might refer to different levels of reality in which the characters are caught. It was also suggested that the particular ending that a viewer remembers or hopes is the definitive one might be linked to the viewer’s relation to the film, depending on race and class positions.

Genre

The intertextuality of the album was described by someone as a ‘web of associations’ riffing off both science fiction film and literature as well as musical influences. In the chat racing alongside our audio discussion innumerable links and connections were suggested. Some of the ones I remember and wrote down were to films such as Westworld, Total Recall, Bladerunner, and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, as well as to the book/film 1984. All these suggest Monáe playing with pre-established genre tropes of memory and control and applying them to the lived condition of Black, queer people in the USA.

We also talked about the connection between Dirty Computer and the genre of cyberpunk. There seemed to be a paradoxical relationship in which the themes of cyberpunk were present, such as the manipulation of memory, but the aesthetic largely missing. A link was made between queer cyberpunk texts such as Raphael Carter’s Fortunate Fall (1996), in the way in which these texts and Dirty Computer envisage technology intervening in and suppressing queer desire.

The different direction of travel between Grimes and Monáe was noted: both use AI and technology as symbols of control but Grimes’ recent work veers into techno-libertarianism, while Monáe uses AI to confront the inequality ingrained within the technology industry, especially with regard to race and gender.

Sexuality

Sexuality was further highlighted as a narrative device for connecting the frame narrative with the individual song videos. Each video contains the same three characters presented as lovers, Jane, Zen, and Ché and are present as major characters in the frame narrative connecting together individual songs and the frame in a queer weave.

It was suggested, through a particularly perceptive reading of the song ‘Pynk’, that queer, Black relations are inherently science fictional because of the ways in which society suppresses and hides queer, Black sexuality. The fact that ‘Pynk’ takes place out in the open, and that the dancers in it wear trousers in the shape of vulvas was seen as a move toward destigmatising queer sexuality and rejection the association between sex and that which is internal, or should be hidden. Someone mentioned that the two dancers without vulva trousers were meant to represent women who don’t have vaginas.

Borders

It was noted that a number of borders were represented both in terms of space and of the body. The narrative seems to exist in some sort of police state in which the actions of individuals are governed by instruments of control, setting up and policing borders of physical space. There appears to be a utopian (or heterotopian) space at the edge of society where the characters experience a freedom from this control, living life without borders both in terms of race and sexuality. It was suggested that this was an appropriation of the American ideal of liberty, so often touted and yet unavailable to Black and minority groups within a racist patriarchal state. The car was read as a particularly evocative symbol of this appropriation of the notion of individual freedom for the marginalised.

The symbol of the door was also brought up, often in different videos marking a boundary between public policed space, and private queer enclaves. This was compared to the use of the symbol of the door we have noted in our discussion of other reading group texts such as Exit West and Rosewater. The song ‘Pynk’ was read as an inversion of this policed public and queer private division, as it makes public queer desire which is often only tolerated by society if it is ‘behind closed doors.’

Memory

Perhaps the most nuanced part of our discussion was around the concept of memory. The frame narrative includes two characters who watch and delete Jane’s memories. It was suggested that these characters used memory to police the boundaries of the self, manipulating and reforming identity by their intervention. Further, we discussed the voyeurism of these two white male characters, watching and then destroying queer, Black memory.

The group was reminded (or told for the first time in my case) that Dirty Computer came second in first choice voting at the Hugos for Best Dramatic Presentation—Short Form, but in the end came close to last after taking into account second preferences, suggesting that those who knew the work rated it highly while others did not know or remember it at all. Who remembers or forgets Dirty Computer tells us a lot about the memory of the sf community.

***

All in all I was greatly cheered by the session. The atmosphere was respectful and encouraging and the discussion was excellent. I was also glad that we could be joined by many people who would normally not be able to take part due to living outside of London. I look forward to the next one. In the meantime, sending love and solidarity to everyone.

Leave a Reply