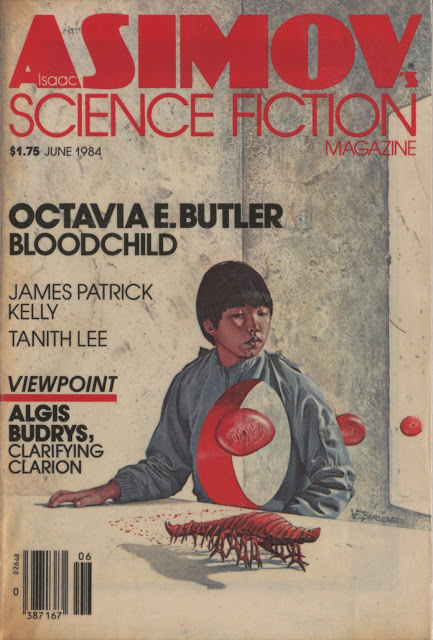

For our first reading group meeting of the year, we read Octavia Butler’s 1984 short story “Bloodchild”. We (the organising committee of LSFRC) chose the text firstly as there has not yet been time to shortlist and vote on the year’s readings (though this is to happen over the next week and a half), and secondly we felt it would be a provocative and stimulating introduction to the year’s theme of bodily boundaries and borders (for a longer explanation of the theme, click here).

We met in the Keynes Library, Birkbeck, on Monday 7th of October. Attendance was strong, and the discussion that ensued was nuanced and wide-ranging. For me, it was our best meeting yet; there were many productive disagreements, which led to insights into the complexity of the text.

For those who have not read it, “Bloodchild” follows the perspective of Gan during an evening in his home. He is a human who is to be the prospective host for the eggs of the alien T’Gatoi. T’Gatoi’s people, the T’lic, have come to an uneasy compromise with human settlers on their planet. After subduing them, the aliens began to use humans as gestators for their young. The T’lic now treat humans as part of their kinship structure, but humans are still subordinated to the aliens. Gan comes face to face with the reality of his future as a human host and must make a decision as to whether he goes ahead with the process.

I will try to put down some of the themes we touched upon, though it certainly cannot reflect the number and depth of opinions/points made by those who attended.

Utopia/Dystopia

We began by thinking through how to place the text within the dystopia/utopia continuum. The text sits uneasily between the two. To a certain extent the symbiotic merging of two alien species is a hopeful and Utopian view of how new kinship structures might be formulated (between humans, humans and animals, humans and aliens!). On the other hand, the bonds between the alien and human characters are unequal; the human characters are manipulated into consent for these relationships/sexual acts, and do not have power over their own bodies/communities. These two readings were summarised as the exploitation (dystopian) and new kinship (utopian) positions. A number of people expressed how this tension was one of the powerful elements of the text.

On another level, the apparently utopian position of pregnant men was challenged; from a transmasculine perspective this is not a fictive or utopian proposition but a potential lived experience, which is doubly disturbing in light of the manipulated consent.

Someone described the story as existing within a present in which past dystopian relations and the future dystopian possibilities ‘are barely fended off’. Humans have previously existed as animal hosts for the T’lic and it seems as though, if they do not behave they might revert to the same state.

Consent

It was felt that consent was a major issue within the story. Although Gan gives his consent to T’Gatoi to impregnate him with her eggs, we are never allowed to see this as freely given. He has been brought up to be a host from birth. His sister is threatened with the act of impregnation when he refuses. He is drugged by eating T’Gatoi’s eggs and by her stingers. T’Gatoi herself is characterised as a successful politician, able to persuade others of her point of view. Then, from a larger systemic perspective, the entire accord between the humans and aliens is based on the production of hosts for the T’lic, with the T’lic in a position of power over the humans. To what extent could Gan ever give consent in this political environment? The highlighting of this power imbalance in the story, could be used to investigate a number of different social relations such as those of class, gender, and race. A provocative thought experiment was proposed; if we were to swap the genders of the major characters, would readers still discuss the consent issues as ambiguous? Probably not, was the conclusion. However, it was pointed out that human women were also manipulated by the aliens. Their ‘job/role’ is to produce more human hosts for the T’lic.

Borders/Bodies

The text is full of the breaching of borders, both bodily and physically. The space between alien and human, human and alien, male and female, is punctured by the relationship between humans and the T’Gatoi, existing as a they do as a symbiotic whole. Someone suggested that the text was a useful way of interrogating disgust; what in particular about the story disgusts us? Is it childbirth? Sex? Insects? Mary Douglas’s thesis of “matter out of place” in Purity and Danger was brought up as a useful way of thinking through body horror aspects of the text, as well as David Cronenberg’s cinematic oeuvre.

It was pointed out also that there were many classic anthropological crossings of boundaries. Gan crosses the boundary from childhood to adulthood. There are many physical crossings of the threshold of the house where the story is set.

Finally, there were geographical/political boundaries that were alluded to in the text. Though the bodily borders were unstable, the power boundaries were still firmly in place, with the humans subordinated to their function of physical hosts for alien offspring. We briefly discussed ‘The Preserve’, the area that humans live within on the planet. The area is ill defined but points to a physical separation between human and alien, which is undermined by the use of humans as hosts. The name of ‘The Preserve’ perhaps alludes to colonial ‘reserves’ for indigenous peoples, or to the idea of a separation being necessary for the ‘preservation’ of human life.

Human/Animal

The category of the human is constantly shifting within the text. The story hints, that before an accord was reached between the T’lic and humans, humans were considered as animals by the T’lic. To a certain extent, within the narrative, humans are still treated as animals or perhaps pets; they do not have power and are kept by the aliens for particular functions. The T’lic are given more, what would be considered ‘human’ characteristics, such as manipulation, politicking, and power play. Such characterisation, it was suggested, questions the category of the human as superior and also our notion of intelligence as an indicator of humanity—the humans are perhaps not as cognitively advanced as their alien partners/overlords. The text enacts a perspective reverse, whereby humans are considered as animals, estranging us from our notions of what it means to be human.

Open/Closed Readings

The ‘Afterword’, published twelve years after the story was first published, was the cause of much discussion. It was felt that Butler’s pronouncements closed down potential readings of the text, especially her comment that the story is not about slavery (one great reading proposed was that the white grubs represented white western ideology sucking the blood from the colonised host). It was suggested that Butler may have resisted this particular view of the story for a number of reasons. Firstly she might not have wanted to map the concept of the alien onto race. Secondly, she might want to avoid being put into the box of ‘black woman writer’ especially after writing Kindred.

Others suggested that the directive to not read the story as an allegory of slavery, rather than closing down meaning, might open it up. Instead of focusing on one particular aspect, Butler’s story is rich ground for considering a number of different issues; such as gender, sexuality, class, human/animal divide, as well as race.

The form of the story itself was thought to facilitate a wide set of readings, structured as it by a series of blanks. We are given very little information about the alien and human cultures, their history, and interaction. The gaps constitute a productive ambiguity, which allows us to think through a host (pun quite possibly intended) of different social inequalities in a complex manner.

Leave a Reply